VNJ Articlesfeaturewildlife

23 August 2022

Wildlife casualties – to treat or not to treat? by Annie Kerr

When working in veterinary practice, staff are often presented with a variety of ill or injured animals, by concerned members of the public. A 2007 RSPCA survey report found that over a two-month period, hedgehogs and birds, such as wood pigeons and doves, were amongst the most frequently treated species at their West Hatch Wildlife Centre. The report highlighted the discrepancy that although 41 per cent of hedgehogs treated at West Hatch were subsequently released, only 15 per cent of carrion crows were eventually returned to the wild.

The report also concluded that many animals are euthanased within 48 hours of presentation and that ‘this is because many casualties are admitted with injuries too severe to enable a successful release back to the wild’. It continues, ‘accurate triage means that [the RSPCA centre] can reduce suffering for those with no hope of recovery, and focus resources to provide the best possible chance to those that can be released’.

So how should veterinary staff decide which animals to admit and treat with a view to rehabilitation and release?

Relevant law

There are two main pieces of legislation that relate directly to the treatment and management of any wild animals presented at a veterinary clinic. The first is the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), 2006, which protects wild animals that are no longer in a wild state from certain acts, for example, unnecessary suffering. The Act states that rehabilitators who care for wild animal casualties will be responsible for these animals for the purposes of the Act.

The Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981, contains information relating to the temporary care and subsequent release of wild animals. The Act defines a ‘wild bird’ and ‘wild animal’ as ‘any bird or animal which was living wild before it was taken into captivity for the purposes of rehabilitation’. Hence, all birds are protected and provisions are made for veterinarians to temporarily house ill or injured birds in Section 4 of the Act. Furthermore, some birds are afforded additional legal protection and a licence is required when they are held in captivity.

However, there are a number of species that cannot be released into the wild and they include any animal that is not normally resident, or a visitor to, the British Isles, and any animal listed on Schedule 9 of the aforementioned Act. Examples of species that cannot be released include the grey squirrel and muntjac deer. Veterinary staff would be advised to familiarise themselves with the detail of Schedule 9 as, for example, the brown rat can be released but the black rat cannot.

There is no legislation which states that veterinary staff must euthanase any so-called ‘pest’ species, for example, rabbits or foxes which are presented to their clinic. These species are subject to the same veterinary and welfare considerations as other sick or injured wild animals.

RCVS perspective

Veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses are obliged to observe the provisions of the current Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons ‘Guide to Professional Conduct’ and in doing so should make animal welfare their overriding consideration at all times. The ‘Guide’ states that veterinary nurses must treat all patients, of whatever species, humanely and with respect and provide suitable nursing care. Veterinary surgeons must not unreasonably refuse to provide first aid and pain relief for any animal of a species treated by the practice during normal working hours and they must do the same for all other species until such time as a more appropriate emergency veterinary service can accept responsibility for the patient.

The ‘Guide’ also prescribes that vets should take into account welfare considerations, the animal’s age, extent of any injuries or disease and the likely quality of life after treatment (rehabilitation and release) when formulating a prognosis. When veterinary staff are attending to an injured or sick wild bird or animal it may be useful to consult an appropriate wildlife rehabilitation centre to gain greater insight into the likelihood of a successful rehabilitation and release.

The ‘Guide’ discusses re-direction of animals to charitable organisations and highlights the need for animal owners or keepers to ‘satisfy the almoning rules of the individual charity to allow the organisation to best utilise its funds and resources’.

Animal sanctuaries

Currently, there is no legislatory control or regulation imposed upon animal sanctuaries, apart from the need to be compliant with existing legislation, such as the Animal Welfare Act, 2006, and the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. However, the Government is considering additional regulation for sanctuaries, which may include local authority licensing and inspection.

The Welfare Offence detailed in Section 9 of the AWA 2006 states that ‘a person commits an offence if he does not take such steps as are reasonable in all the circumstances to ensure that the needs of an animal for which he is responsible are met to the extent required by good practice’. The RSPCA has published a booklet entitled, ‘Animal Welfare Act 2006: Guidance for Wildlife Rehabilitators’, which addresses issues relating to the care and rehabilitation of wild birds and animals and discusses the welfare implications of confinement and release.

Guide for veterinary staff

The RCVS suggests that all veterinary surgeons should provide emergency treatment for wildlife casualties and that such care enhances the public perception of the profession. However, individual practices may devise their own admission and management procedures for the different wildlife species that they commonly encounter in their area. Examples of protocols which staff may find useful include:

• details relating to the species in question (for example, identification, habitat) and its legal status

• specific first aid and pain relief for various wildlife species

• handling and nursing care for various wildlife species

• a list of local wildlife rehabilitation centres.

An article by Kirkwood and Best (1998) may be useful reference material for veterinary staff when designing protocols and considering the ethical issues relating to wildlife casualties.

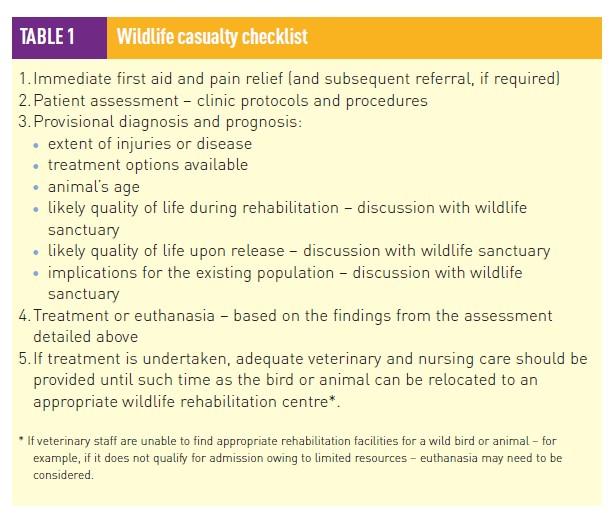

Finally, a sample checklist that could be used by veterinary staff when treating wildlife casualties is provided in Table 1.

Summary

As discussed in the ‘Guide to Professional Conduct’, while members of the veterinary team have different roles within clinical veterinary practice, the professional responsibilities of veterinary nurses are similar to those of veterinary surgeons. Staff must communicate with colleagues within the organisation to co-ordinate the care of patients and the delivery of veterinary services and they must regularly review work within the team to ensure the health and welfare of patients – wild or otherwise.

Author

Annie Kerr

BSc(Vet) BVMS MRCVS CertWEL

Annie Kerr graduated from Murdoch University in 1999 and worked in veterinary practice in Australia and England before accepting a clinical training scholarship, funded by Oldacre, at the University of Bristol in 2006. She holds the RCVS Certificate in Animal Welfare Science, Ethics and Law.

References

1. RSCPA (2007) Review of outcomes of admissions to the centre, Oct 07, http://www.rspca-westhatch-wildlifecentre.co.uk/ news%20sept%20oct%2007.htm#admrev, Accessed April 15, 2009

2. OPSI (2009) Animal Welfare Act, 2006. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2006/pdf/ukpga_2 0060045_en.pdf, Accessed April 1 5 2009.

3. OPSI (2009) Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/RevisedStatutes/Acts/ukpca/1981/cukpga_19810069_en_1, Accessed April 15, 2009

4. RCVS (2009) Guide to Professional Conduct: Vets – http://www.rcvs.org.uk/Templates/Internal.asp?NodeID=89642, Vet nurses – http://www.rcvs.org.uk/Templates/Internal.asp?NodeID=96850, Accessed April 15 2009.

5. RSCPA (2007) Animal Welfare Act, 2006: Guidance for Wildlife Rehabilitators http://www.rspca.org.uk/servlet/ContentServer?pagename = RSPCA/RSPCARedirect&pg=WildllfeRepcrtsandResources, Accessed April 15 2009

6. MULLINEAUX, E., BEST, R. and COOPER, J. E. (2003) BSAVA Manual of British Wildlife Casualties. Blackwell Publishing

7. KIRKWOOD, J. and BEST, R. (1998) Treatment and rehabilitation of wildlife casualties: legal and ethical aspects. In Practice 20: 214 – 216

• VOL 25 • No1 • January 2010 • Veterinary Nursing Journal